On January 7, 2015, a pair of brothers, Chérif and Saïd Kouachi, set out and successfully attacked the offices of the French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo, murdering 11 journalists, a bodyguard, and a building caretaker. The attackers called out several cartoonists and journalists by name upon entering the room where the staff was holding an editorial meeting, including editor Stéphane (“Charb”) Charbonnier, cartoonists Jean (“Cabu”) Cabut, Georges (“Wolin”) Wolinski, Bernard (“Tignous”) Verlhac, and Philippe (“Honoré”) Honoré. The attackers also killed Charlie Hebdo columnists Bernard Maris and Elsa Cayat, copy editor Mustapha Ourrad, and journalist Michel Renaud, a guest at the meeting.

The attack lasted between five and ten minutes, in which the Koachi brothers also killed police officer Ahmed Merabet while fleeing the scene. An intense search ensued, and the attackers would eventually hole up in a print shop before dying in a subsequent shootout.

Chérif and Saïd Kouachi were explicit in their motivations for their heinous act of terrorism. Their bloodlust was inspired by Charlie Hebdo’s publication of cartoons seen as disparaging and blasphemous of Islam and the prophet Muhammad. The Kouachis said they were directed by al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), a Yemen-based militant group considered a terrorist organization by the United States, Canada, Australia, the United Nations, and Saudi Arabia, among others.

Charlie Hebdo was no stranger to violent retaliation. Its offices were firebombed, and its website was hacked in November 2011, presumably in response to issue 1011, when it renamed the publication “Charia Hebdo,” a reference to Sharia law, and featured a cover depicting Muhammad.

The brutal and bloody act of terrorism galvanized the L’Hexagone and the rest of the Western world. Not only had the AQAP-directed brothers fired upon Charlie Hedbo, but they had also taken aim at satire itself, a beloved and longstanding form of expression in France, dating back centuries to the days of court jesters with permission to mock the king and others in power. Satirical works mocking the French aristocracy would play a significant role during the French Revolution, with Charlie Hebdo keeping the irreverent and sharp-tongued tradition alive in modern times.

As a show of solidarity, the French took to the streets in the aftermath of the Charlie Hedbo murders and a related attack in a nearby Hypercacher kosher supermarket. Millions took to the streets throughout France, with thousands more in cities abroad. “Je suis Charlie,” French for “I am Charlie,” became a slogan expressing support for the freedom of expression and the press, borne out of a simple graphic designer Joachim Roncin created in response to the tragic events that happened five minutes away from his home.

While the brutal attack targeted Charlie Hedbo specifically, the world saw it as an affront to the notions of free expression, an unencumbered press speaking truth to power, and liberty itself. These are values nations like France and the United States view as paramount and necessary to preserve an often fragile democratic republic, or at least pay a lot of lip service to.

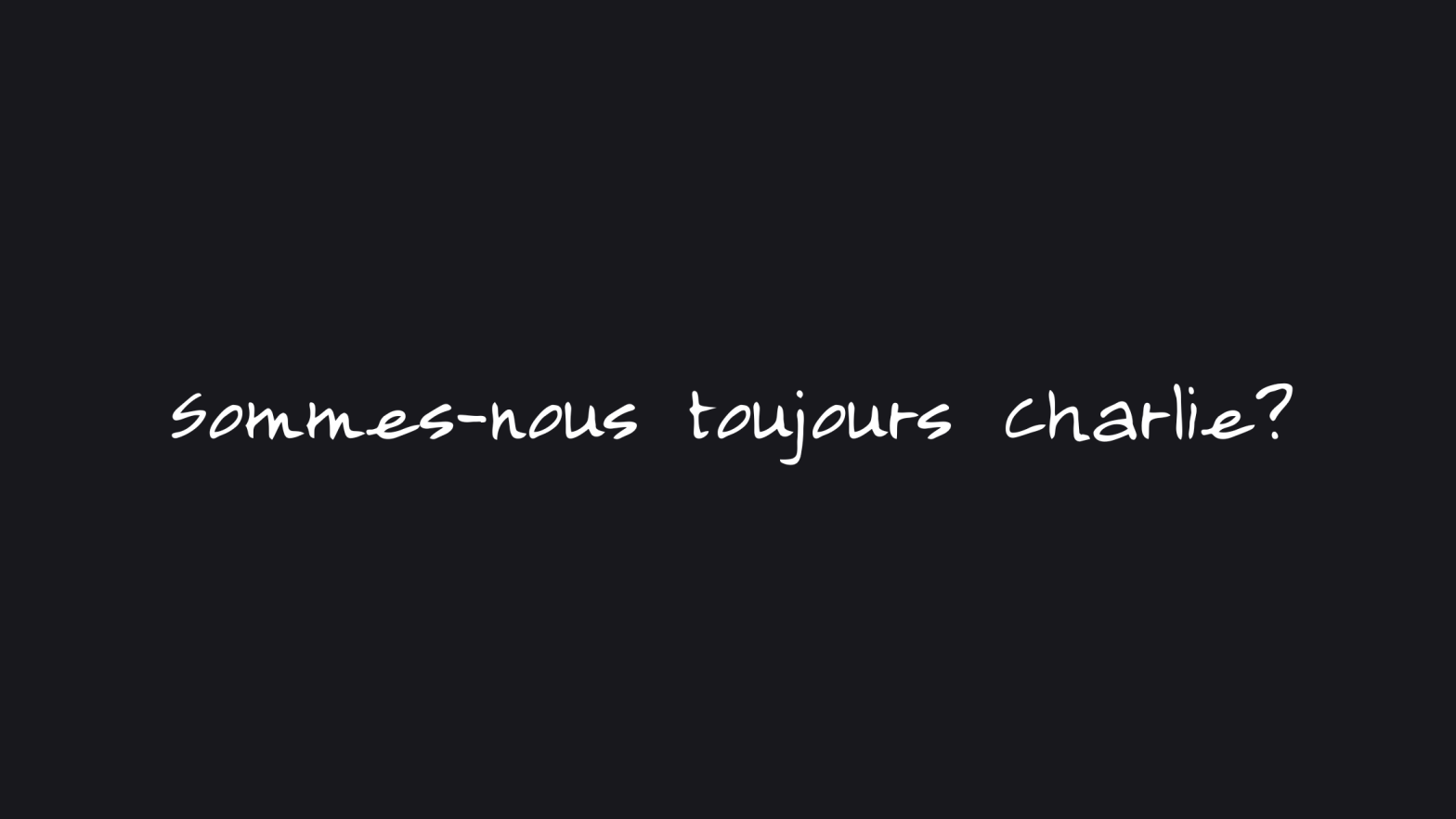

But has the Esprit de Charlie waned in the ten years since those horrific acts of terror? Are cartoonists and journalists like those at Charlie Hedbo still free or safe to ply their satirical craft to shine a light on the actions of those in positions of power and influence? Should it even matter to those devoted to the role of journalist?

Satire has a virtue that has helped us to go through these tragic years: optimism. If you want to laugh, it’s because you want to live. Laughter, irony, and caricature are expressions of optimism. Whatever happens, dramatic or happy, the urge to laugh will never disappear.

Laurent “Riss” Sourisseau, editor, Charlie Hebdo

Not at Charlie Hebdo. Ten years on, the staff at the weekly newspaper hasn’t stopped being just as acerbic in its critique of those with influence and power, including Islamic fundamentalists and far-right politicians. They commemorated the tenth anniversary of the fatal attacks with a special edition sporting a cover depicting a grinning reader sitting atop a rifle similar to those used by the Kouachi brothers with a headline exclaiming, “Indestructible!”

“Today, Charlie Hebdo’s values, such as humor, satire, freedom of expression, ecology, secularism, and feminism, to name a few, have never been so challenged,” writes Charlie Hebdo editor Laurent “Riss” Sourisseau, who survived the attack. “Perhaps it is because renewed obscurantist forces are threatening democracy itself. Satire has a virtue that has helped us to go through these tragic years: optimism. If you want to laugh, it’s because you want to live. Laughter, irony, and caricature are expressions of optimism. Whatever happens, dramatic or happy, the urge to laugh will never disappear.”

Who are some of those “obscurantist forces” today? In the United States, billionaires like Jeff Bezos, Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong, Elon Musk, and Mark Zuckerberg. These men—because, of course, they’re men—own some of the most prominent newspapers in the country or the largest social media platforms, and they aren’t shy of exerting editorial influence and control to further their financial interests and political ideologies.

The Washington Post, owned by Amazon and Blue Origin founder and weak IRL imitation of Lex Luthor, Jeff Bezos, recently killed a piece by Pulitzer-prize-winning cartoonist Anna Telnaes. The cartoon depicted billionaires Bezos, Musk, Soon-Shiong, Sam Altman (OpenAI CEO), and Mickey Mouse (representing Disney/ABC) making an offering to a yuge statute of Donald Trump. Telnaes’ cartoon is a commentary on the recent pilgrimages to Mar-a-Lago by these billionaires to ingratiate themselves with the incoming president, presumably because their firms have lucrative government contracts they’d like to keep and are acquainted with the capricious and vindictive nature of The Donald.

Telnaes resigned from her position at The Washington Post, a newspaper that adopted the slogan “A Democracy Dies In Darkness.” The resignation follows the newspaper’s decision not to endorse a presidential candidate in the 2024 election. Publisher William Lewis said the decision, less than two weeks from Election Day, was a “return to the newspaper’s roots.” However, it’s hard to see this as anything other than a capitulation to Trump, at least for the troves of angry readers who canceled their subscriptions.

It’s hard to imagine the current iteration of the The Post having the metaphorical cojones to go after President Trump in the spirit it went after Tricky Dick.

There was a time when The Washington Post stood up to presidents overstepping the law through investigative reporting by Bob Woodward, Carl Bernstein, and others. They did so despite the risk of retaliation by the Nixon administration. Ultimately, the courage and dogged reporting informed the public of the Watergate Scandal and played a significant role in the toppling of a corrupt president.

It’s hard to imagine the current iteration of The Post having the metaphorical cojones to go after President Trump in the spirit it went after Tricky Dick.

Los Angeles Times billionaire owner Patrick Soon-Shiong also prevented its editorial board from endorsing a presidential candidate. Like The Post’s move to stifle a Harris endorsement, this move was seen as an abdication of the press’s role in informing the public when many felt American democracy was vulnerable.

It isn’t just legacy media bending the knee out of presumably financial interests to Trump. Since taking over Twitter—I will never call it “X” because that’s a stupid rebrand—Musk has actively manipulated the algorithm to prioritize his musings and other posts aligning with his ideology, seized user handles for his interests, and removed blue checkmarks from people who say mean things he doesn’t like, including calling into question his gaming prowess.

Subscribers canceling their Washington Post and LAT subscriptions, users migrating to Blue Sky from Twitter, and cartoonists and editors resigning in protest show that the piles of cash billionaire publishers can’t snuff out the fire in journalists devoted to speaking the truth despite the real risk of retaliation from the incoming administration and its rich bootlickers. Nor has the appetite for that journalism and criticism been Ozempic’d from the public.

Now, more than ever, je suis Charlie, indeed.

Rudy Sanchez is a writer and product marketing consultant based in Southern California. Once described by a friend as her “technology life coach,” he is a techie and avid lifelong gamer. When he’s not writing or helping clients improve their products, Rudy is playing Rocket League, running laps in Gran Turismo, or deep into a YouTube rabbit hole.