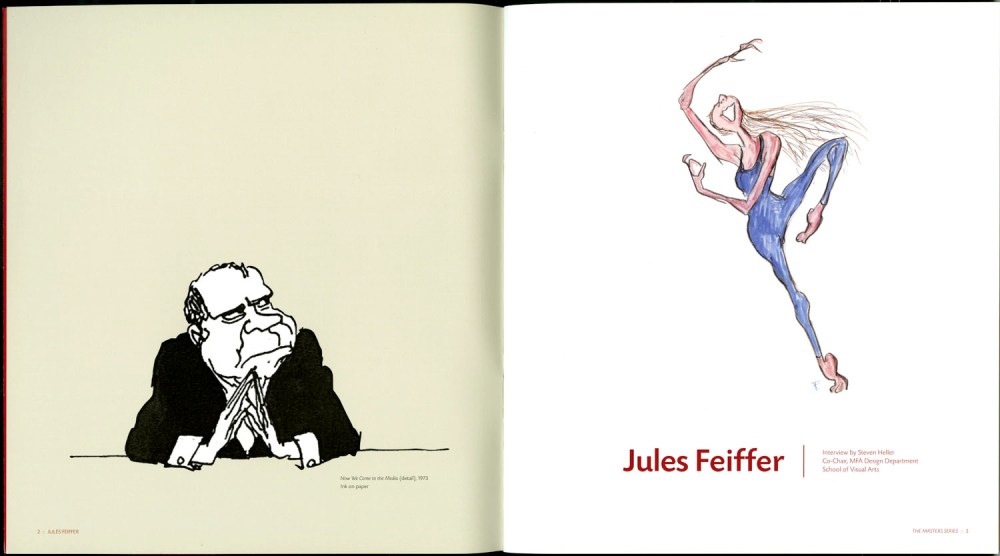

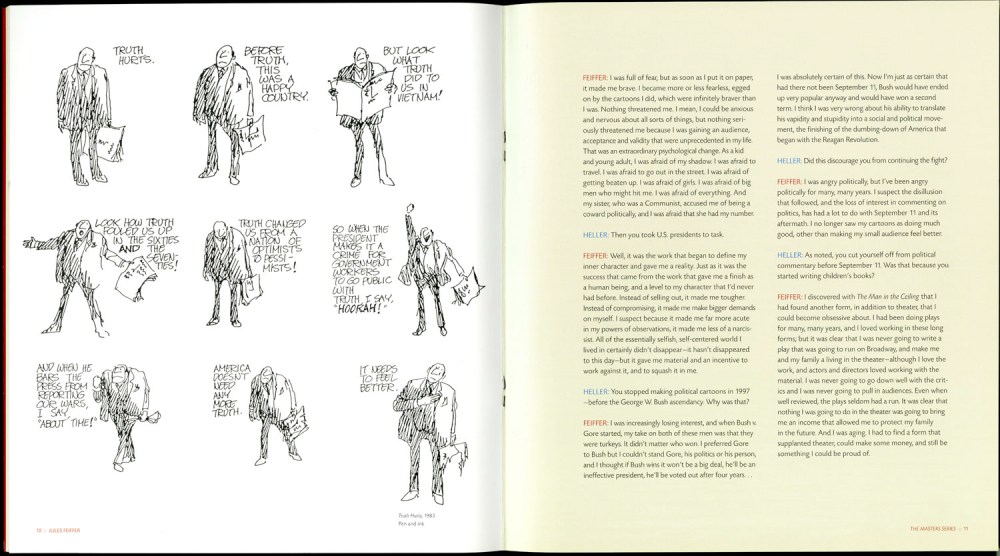

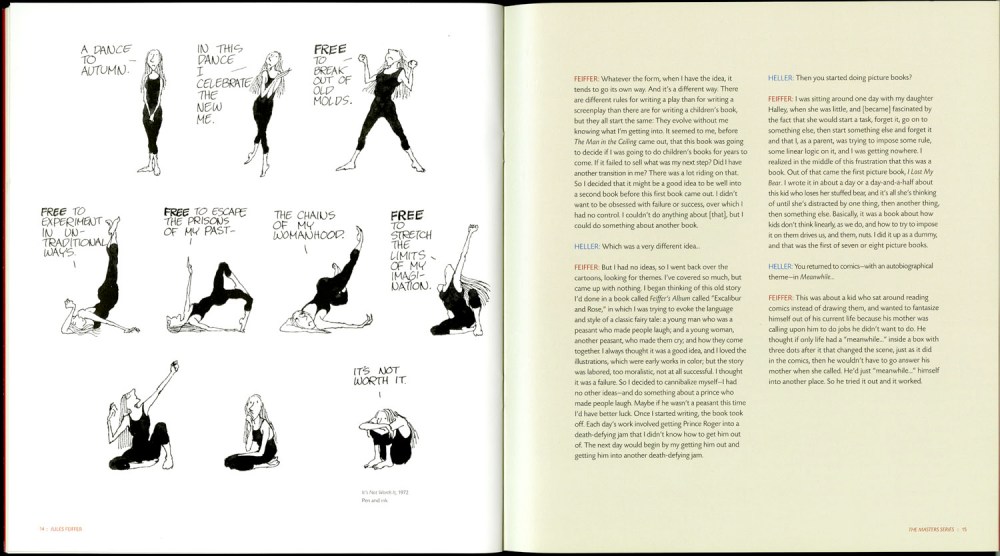

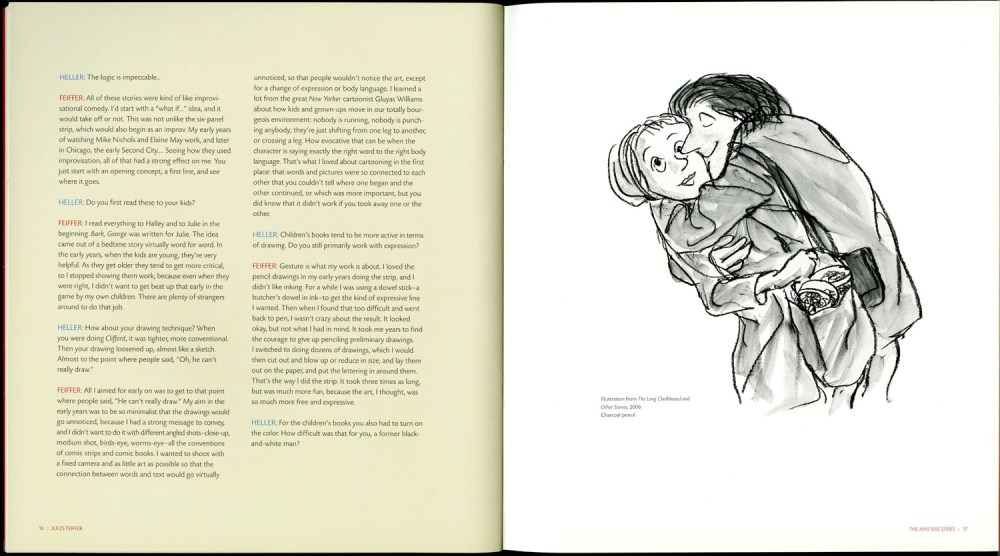

Jules Feiffer, 95, my comics mentor and socio-satiric hero, died yesterday at his home near Cooperstown, NY, where he and his wife, Joan, lived. I knew by the laws of nature that he didn’t have a lot of time left. So I jumped at the chance to speak to him on Zoom this past fall; he was happy, funny and sharp, and he thanked me for having contributed greatly to his 25th-anniversary cartoon anthology, Jules Feiffer’s America: From Eisenhower to Reagan. I published our exchange here, and prior to that I randomly wrote an appreciation not pegged to any newsworthy event, just a showing of affection for him.

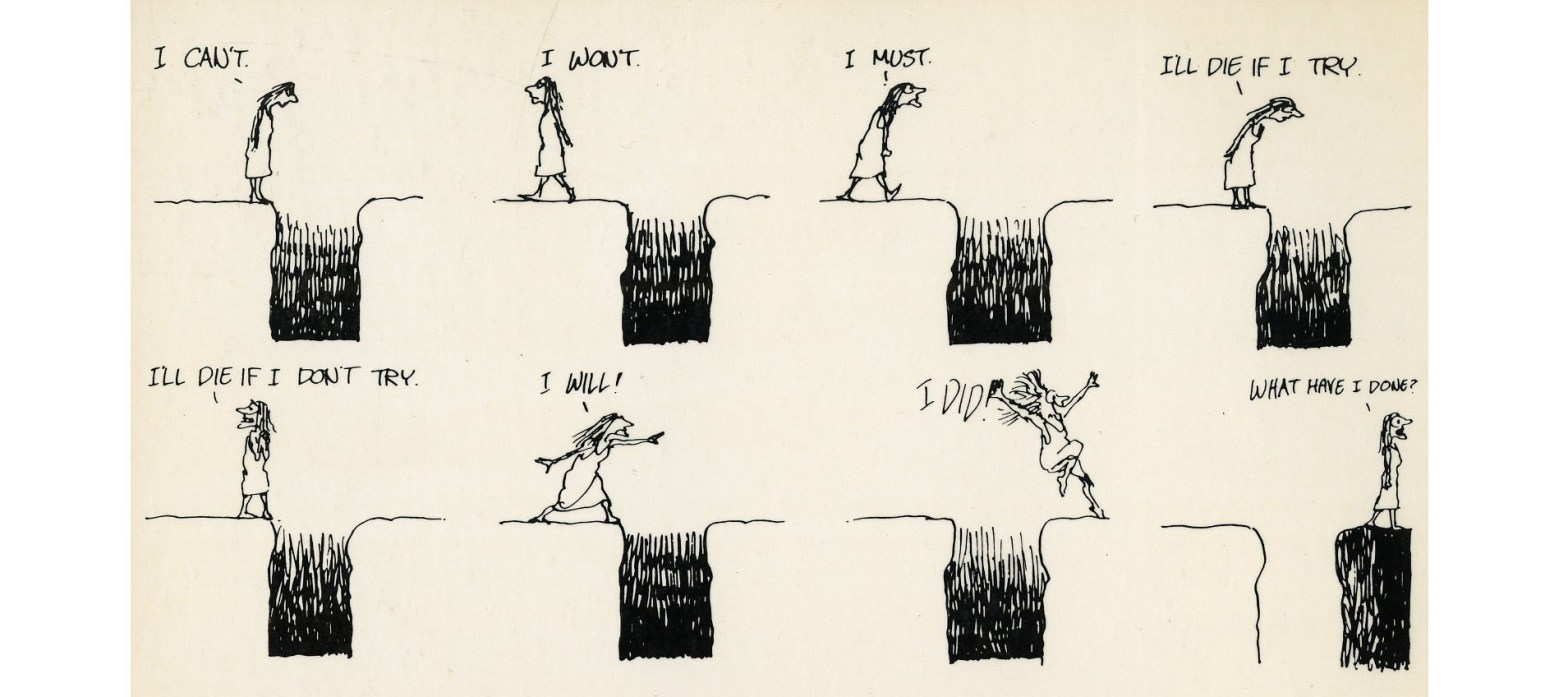

Feiffer’s art (and writing) was what made me want to become a cartoonist—a goal I never attained, even though as a student I was enrolled in Harvey Kurtzman’s SVA comics class. Nonetheless, I briefly drew panel-less cartoons because Feiffer did. I delved into my neuroses for content because Feiffer did. But I never mastered his acerbic genius of mixing drawing and world-weary angst. I did, however, get to know Feiffer, and edited his abundant work with him for the book. As a perk I got to meet some luminaries, including Shelley Duvall and Robin Williams, after Feiffer’s screenplay for Popeye was released. I also had the good fortune of spending time at his Martha’s Vineyard home, an epicenter for some of his extraordinary circle of friends from art, theater, film, journalism and politics.

Feiffer had a rich, creative and amazing personal life, with the usual ups and downs that make a humorist, playwright, novelist and screenplay author so good at capturing the inner and outer depths of troubled yet symbolically autobiographical characters.

Before he passed, Jules was working on an autobiographical graphic memoir, which he described in our interview this past fall. As a bookend, I’m republishing the 2010 review I did of his first autobiography.

Backing Into Forward: A Memoir

By Jules Feiffer (Nan Talese / Doubleday)

I have known Jules Feiffer, the cartoonist, playwright, screenwriter and novelist, for 25 years. Even before that, starting when I was a 10-year-old wanna-be cartoonist, I dreamed of doing work like him (and did so for a few years). So it came as quite a big surprise—in fact, a shock—when I read in his splendid 400-plus-page memoir that his cousin was Roy Cohn, the legal counsel and chief inquisitor for the notorious red-baiter, Senator Joseph McCarthy.

How could that fact not have come up in conversations, especially since Feiffer knew I was fascinated with McCarthyism, and I co-authored a book called Red Scared? What’s more, for lefties and liberals there was no more nefarious person from the ’50s, when he wielded the power to ruin lives, through the ’80s, when he was a denizen of Studio 54. Roy Cohn was the devil.

That revelation is one of the things that makes this hefty book a real page-turner. This one small tidbit, combined with many other candid tidbits, insights and confessions gives those of us who know him and those who just know his work—and those who never sampled his brilliance before (which is unlikely since his work has touched so many lives)—an inspiring portrait of one of the most important satirists of the second half of the 20th century.

Memoirs can sometimes be an overgrown jungle, forcing a reader to plod and meander through heavy underbrush of chronological recollections, both meaningful and trivial. Feiffer’s book, sprinkled throughout with cartoons and photos, moves swiftly through his childhood formative career years and current life at 80 (believe me, he’s no 80-year-old that you or I can imagine). Though logically and rhythmically arranged, this book is not doggedly tied to a timeline.

Along the way, we learn that much of his insightful humor and intense social consciousness was formed by complicated relationships with his domineering Jewish mother, Rhoda (a failed aspiring dress designer, who made exquisite drawings, and also emasculated his father, Dave); a Stalinist sister, Mimi (as dogmatic about politics as they came); and ultimately friendships with the likes of director Mike Nichols (who directed, among other things, Feiffer’s paradigm-shifting coming-of-age film Carnal Knowledge), actor/director Alan Arkin (who directed his first politically charged play “Little Murders”) and a slew of other New York intellectuals, entertainers and artists—some of the best fly-on-the-wall-ism in the book.

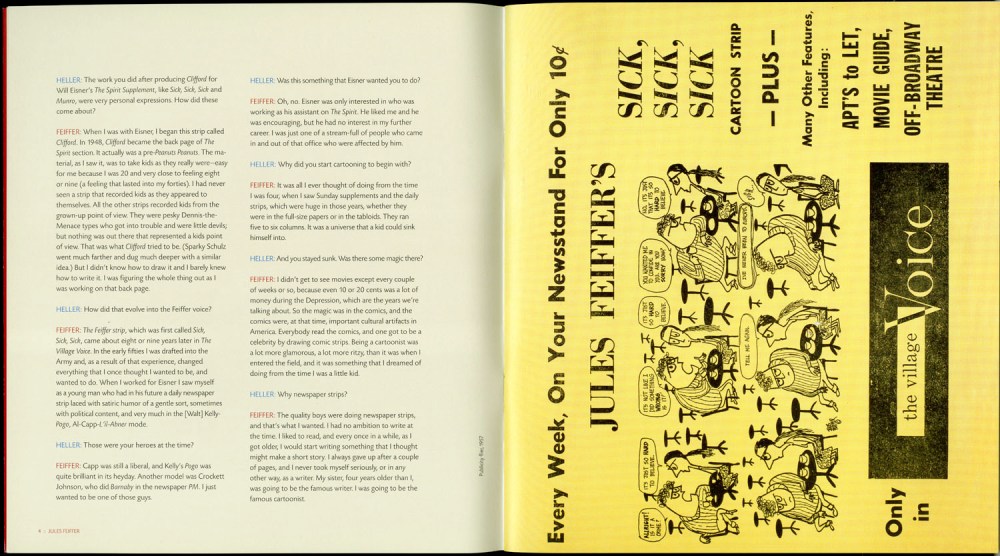

The memoir works on four levels. The first is the requisite spewing of pent-up interfamily resentments. But rather than voyeuristically listening in on Feiffer at one of his psychotherapy sessions, his anger is cut with humor and pathos in a voice that accentuates the pain while accepting the inevitability of where it all led. The second is a professional biography (expressed with wit and humanity) that examines the evolution of the Feiffer style and methodology—his passion for comics (he worked for Will Eisner for three early years). He also makes clear the risk he took in the development of his brand of psychoanalytic, self-deprecating humor that was unique in the ’50s. It was championed by Feiffer, Mike Nichols and Elaine May, Philip Roth and Lenny Bruce, and gave way to Woody Allen. The third level is how politics became an over-arching concern given the tenor of the anti-Communist fear (which makes having Roy Cohen even more tragically absurd, owing to Feiffer’s left-wing and early anti-Vietnam stances). Then the fourth, the part I found the most moving given the tenor of his ’60s-era cartoons (which professed a kind of fear and hatred of women), was the utter love and warmth he has for his wife and children. Indeed, at her own request, Feiffer’s second wife, writer-comedienne Jenny Allen [he later married Joan Holden] is barely mentioned in the book, except by way of loving explanation for why he respected her wishes.

What a great memoir does is reveal those shared personal or professional traits that contribute to a better understanding of why the reader cares about the author in the first place. I used to think that Feiffer’s cartoons—and later his plays—echoed my own life, or at least the neurotic parts of it. This book is often a mirror—not in a narcissistic way, but in a “yes, this is indeed why I have admired Feiffer’s work for much of my life—and continue to do so” way.