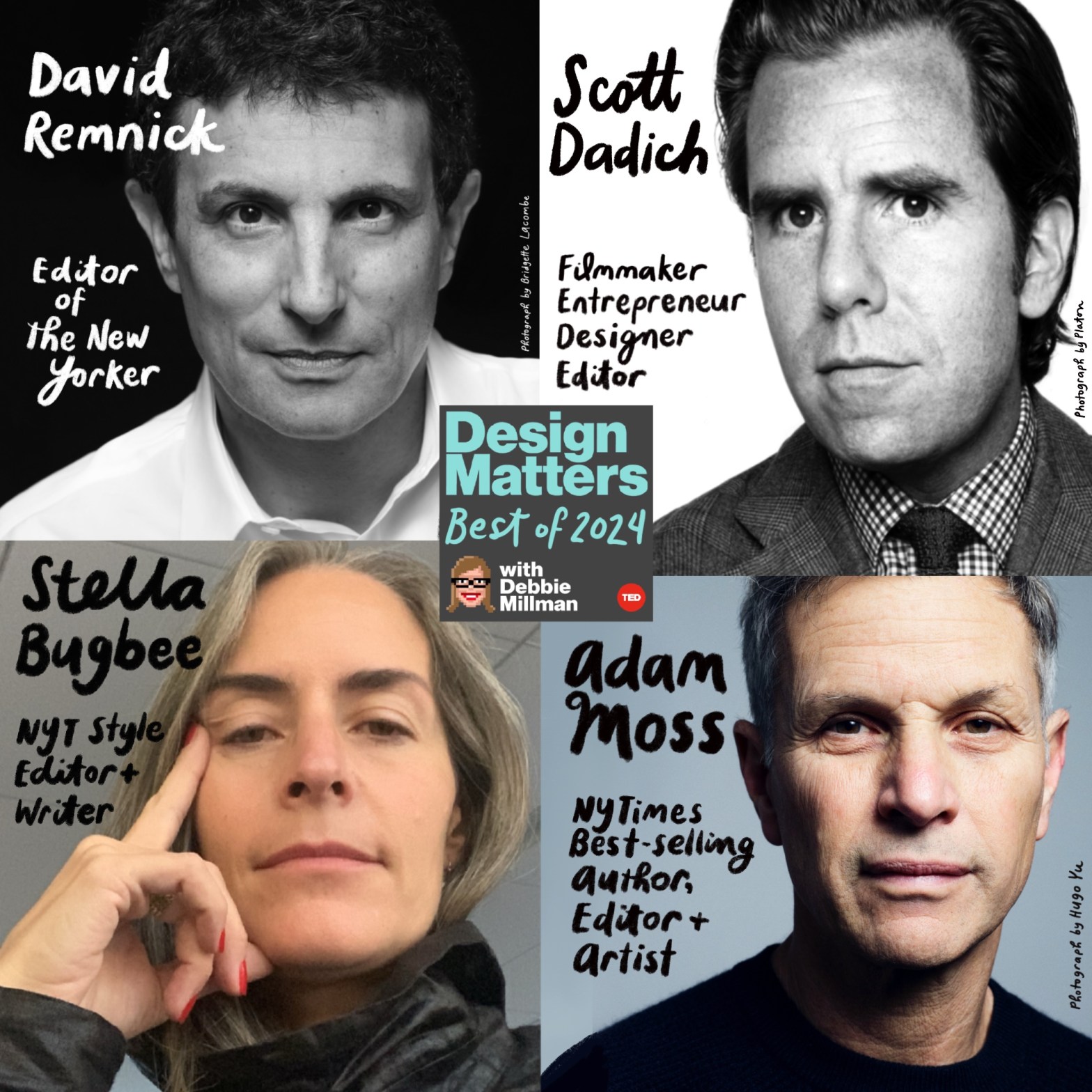

On this special episode of Design Matters, we look back at the collective brilliance of editors interviewed in 2024. Best of Design Matters 2024 with Stella Bugbee, Scott Dadich, Adam Moss, and David Remnick is live!

Stella Bugbee:

My main goal was to create a space where the people working on that project could say whatever they wanted to say in the tone they wanted to say it in.

Adam Moss:

And then they said, “Bob wants a cover.” I said, “Bob wants a cover. We have dogs on the cover.”

Curtis Fox:

From the TED Audio Collective, this is Design Matters with Debbie Millman. On Design Matters, Debbie talks with designers and other creative people about what they do, how they got to be who they are and what they’re thinking about and working on. To mark the end of 2024, on this episode, we’re going to hear excerpts from interviews Debbie did with magazine editors in the past year or so.

Adam Moss:

I had no experience. I mean zero experience.

Scott Dadich:

We left no digital signatures. We checked in with that hotel and we waited.

Speaker 3:

For many years now, Debbie has been interviewing designers, artists, writers, filmmakers, musicians, people in pretty much every creative field. In the past year or so, it just so happens that she interviewed some of the best magazine editors in the business. In this episode, we’re going to hear excerpts from those interviews. First up, Stella Bugbee, the Styles Editor at the New York Times since 2021. Before that, Stella Bugbee was the editor of New York Magazine’s website, The Cut.

Debbie Millman:

You started working at the New York Magazine‘s The Cut as a consultant in 2011, first to help relaunch New York Magazine‘s digital vertical. You ended up agreeing to join as the editorial director the next year, and in the 10 years you were there, you essentially reconstructed what was originally a Fashion Week blog and created a full-fledged magazine brand in its own right. What gave you the sense that you could do that aside from just always wanting to be in charge?

Stella Bugbee:

Well, so New York Magazine has actually a precedent for a project like this, and that is Ms.

Debbie Millman:

Ms., Ms Magazine.

Stella Bugbee:

And Adam Moss, who was the Editor at New York Mag, I think that he thought there was space to push this whatever he was calling it, we were calling it a women’s vertical or whatever, into a vital internet publication. I stress the internet part of it because I think there was this permissiveness to give somebody maybe untested a chance, and that was the writers, that was the editors, that was the photo team. It wasn’t a whole bunch of experts coming in who’d already done a bunch of stuff. It was a bunch of young people and we didn’t necessarily know exactly what the rules were, so that was good. I’m not sure that I had the confidence necessarily to come in and do that, but there was a lot of interest in pushing things and Adam was very experimental. And I had worked with David Haskell, who is now the editor-in-chief of the magazine On Topic, which was his project that you mentioned earlier. And then when we worked on topic, I remember thinking, I just actually want to be picking the topics.

It was Rob, Jean, Piccho, and me and David. And while I was of course interested in the design, I was so much more interested in thinking about assigning stories for a specific topic or picking the topic and then thinking about how to represent that. So David, he knew that that’s where my interests lay. Plus, I’d been working in fashion then for a year at that point before that, and it just was a strange job, and I had a strange resume, and it enabled me to pull upon everything I’d done up to that point. It let me pull the branding and the art direction and the editorial ideas and put them all in one place, which lucky, so lucky to be able to use all these weird experiences that didn’t necessarily add up to anything until that moment. So it wasn’t necessarily that I had the confidence, just I had a really strange group of skills that applied in this particular instance, and then I ran at it head on.

Debbie Millman:

I found this quote, something that Adam Moss said about you when he hired you. “The very unusual thing about Stella is that she has this big important editorial job and has never been an editor before.” He went on to state that he would’ve been unlikely to appoint a design director to run The Cut had he not already gotten to know you when you consulted. And he stated, “What we saw then was that Stella was a natural editor with a crystal clear vision and incredible sense of story and great news judgment.”

Stella, what I love so much about this is that you succeeded by creating a magazine and a brand that you’ve described at various times as a “smart, funny, clear-eyed look at fashion, beauty, and issues that matter most to women that also blends a literary feeling with a punk feminist sensibility.” What could be better than that? How were you able to figure it out and then sell it in such a clear-eyed way? I mean, that’s what he said, in a clear-eyed way.

Stella Bugbee:

My main goal was to create a space where the people working on that project could say whatever they wanted to say in the tone they wanted to say it in. So it was always very much about the community. I used to make this arm motion where I put my arm in a circle and I said, “I’m just keeping the space open so that we can do what we want and say what we want, and that we’re not being forced into a silo by some advertising category.” I think that’s, really, if you look at most magazines, they were created for the purpose of advertising categories.

Debbie Millman:

And you created this for a certain sensibility, it feels, like an attitude almost.

Stella Bugbee:

Yeah, psychographic, I say. But I firmly believe that there were people who wanted to talk about serious things and silly things at the same time in the same place, and that was fine. And I defended that urge more than anything, and it changed dramatically year over year over year. And so it wasn’t just that I had that vision from the beginning. It was like a, “Well, I got that done. What else can we do and how else can we grow? And who else can we bring on and what other voices can we put forth and what other challenges and ideas?” And while that was all happening, the magazine was also feeding me incredible pieces. And I was working with the people who worked making the print magazine all the time and the editors on that. And I had an incredible partner in Lauren Kern who’s now at Apple News, and she was my editorial partner on the magazine on the print side.

And once that came about, when she joined, I think that we all saw the real potential for it to be something very impactful. And again, we just all ran at it. For me, I didn’t want to squander that opportunity ever at any moment. I thought, what if no one ever gives me this opportunity [inaudible 00:07:31] run at this? And I wanted to give everybody else that sense that we got to run at this because we don’t know that this is a guarantee that we’ll always have a place to say and think and be ourselves, even with the precedent of Ms. having come out of that publication, which is really powerful. And I was operating a lot on other publications’ backs. I think you mentioned Mirabella, the actual Mirabella.

Debbie Millman:

Right. Grace’s [inaudible 00:08:00].

Stella Bugbee:

[inaudible 00:08:00] was incredible magazine. Fassi, there was a precedent for some of what we were doing.

Debbie Millman:

Remember New York Woman?

Stella Bugbee:

New York Woman, yeah. And in fact, I met with the editor of New York Woman early on in my time at The Cut because Pam [inaudible 00:08:14] knew her. We went out for lunch. And it was important to me to note that we were part of a pretty healthy legacy, actually, and we were just doing it on the internet for a new audience and building an audience in that space. But a lot of people have tried to do what we were trying to do. And in fact, I have the very first issue of Mirabella and I got it when we were relaunching The Cut in 2018, just as a reference. And I couldn’t believe how contemporary it was and how it felt like it could literally be running now.

Curtis Fox:

Stella Bugbee, she mentioned her editor at New York Magazine, Adam Moss. Debbie interviewed Adam Moss in May of this year, and they talked about how he reshaped New York Magazine and then about the family of magazine websites created under his editorial direction.

Debbie Millman:

You left the Times in the early aughts, but not after more accolades, awards and increase in readership, a whole different way of really assessing the magazine. And you went on to New York Magazine as editor, and you were brought in again to remake it by then owner Bruce Wasserstein. And I read that you approached it as a restoration project as opposed to a re-imagination, and you wanted to bring back some of the values of the original co-founders, Clay Felker and Milton Glaser, while still pointing it to the future. What were the values you deemed most important to restore?

Adam Moss:

Well, one of them was both Clay and Milton had a perspective that what the magazine was really about was not New York City, but a New York City way of looking at the world. And that there was a filter that could be applied to Washington, could be applied to Hollywood, could be applied overseas to London, other places, that it was really a magazine of the cosmopolitan world. New York Magazine inspired a lot of city magazines, but it actually never was a city magazine. And the owners of the magazine before Bruce took it over very much remade it themselves in the mold of the magazines that were imitators of New York. So I was trying to go back to that original idea, which I thought was bigger and more interesting and more adventurous, and to remake the magazine in 2004 to feel like it was a magazine of 2004, but it had the values that animated its founding.

Debbie Millman:

Adam, we could do a whole series on Design Matters about the relaunch of New York Magazine, but I do want to get to your glorious new book. Suffice it to say that since the redesign and relaunch in 2004, New York Magazine has won more national magazine awards than any other publication, including the Award for General Excellence in 2006, ’07, 2010, 2011, 2014, 2016, as well as the Society of Publication Designers Award for 2013 Magazine of the Year. Most recently, the magazine won a George Polk Award in magazine reporting for the Bill Cosby Rape Investigation, and it’s also been awarded several Pulitzer Prizes.

Adam Moss:

Many after I left, I just should say.

Debbie Millman:

Okay. [inaudible 00:11:36].

Adam Moss:

But yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, yes. Thank you.

Debbie Millman:

Congratulations.

Adam Moss:

Thank you.

Debbie Millman:

You not only re-imagined the print magazine, you also embraced the magazine killer called the internet and new digital-only brands, five of which, Vulture, The Cut, Intelligencer, The Strategist and Grub Street are now considered heavyweights in modern online editorial. And New York Magazine is now as much of a digital company as it is a print company.

Adam Moss:

Absolutely, yeah.

Debbie Millman:

When so many editors couldn’t or wouldn’t adapt their publications to the digital world, what gave you the sense that this was going to be the game changer it ended up becoming?

Adam Moss:

It wasn’t that I thought it was a game-changer. It was that I thought that it was interesting. And I had come from the New York Times just recently, which had, they were making a few mistakes, but basically they were getting it right about how to create a digital newspaper. And I found that very exciting. And there were several experiments even at the very early newyorktimes.com that I did with the magazine that were exciting to me. I wanted to bring that spirit. I just wasn’t scared of it. And also, the owners of New York Magazine were not scared of the internet for reasons that really, I’ve told this story too many times and it’s boring, but they were making money on their own digital site for arcane reasons, but they were so that became a business imperative too. And really, I just keep saying this not because I’m an economist, but you need the right conditions on the ground to do anything creative really.

And in all these instances, the right conditions, the right economic conditions enabled the creative things that we were able to do, but I was just crazy interested in it. And each experiment we did trying to build out a satellite, not a satellite, but a constellation really of digital magazines, was interesting to me and interesting to my colleagues, and it spurred us on to do more and more and more. We started with this thing called Grub Street about food. And then we realized, well, okay, if these things were vertical as opposed to horizontal, which is to say about one subject, that could be wonderful, and maybe the voice should be the same voice as the print magazine, but sped up for digital purposes and gave a lot of license to the early writers who helped create the voice.

Grub Street became Intelligencer, which eventually became Vulture on culture and entertainment, and Intelligencer went through several iterations, but eventually became a news site, and then The Cut, which was a women’s magazine, but a very different women’s magazine than had never been made before. And lo and behold, we had this fleet of magazines that were built for the internet and had the DNA of New York in them, and that proved to really work.

Debbie Millman:

In 2019, after 15 years of nonstop growth and innovation, you decided to leave New York Magazine. At that point, you had also somewhat secretly taken a painting. Did your new fine arts pursuit influence your departure?

Adam Moss:

No. I don’t think so. I had always loved the visual parts of magazine making, and I have a house in Cape Cod that used to be an art school just by coincidence. And there is just a feeling of being there that you can see the ladies with their bonnets painting on plein air on the dune, and I found that interesting. And then one summer I just decided to try to do a painting a day. I had no experience, I mean zero experience doing this, and I just started to experiment. Started painting at 3:00 and ended at 5:00. Whatever it was, it was. And that was crazy fun to me. Then when I got back to New York, someone made a gift of giving me an art teacher, and that was the first time I got a teacher. But I was still working in New York at the time.

No, I left New York because I felt that I could only edit the magazine for myself and that I was no longer the reader. I had seen the ways in which an editor who didn’t have themselves as a compass could screw up a magazine and how it could become contagious. I just didn’t want to do that. So I had to get out of the way. So I left without any sense of what I’d want to do, except as you’ve mentioned before, to try to do something with less ambition. It was more like, okay, let’s see what happens without any true sense. But I did enjoy painting enough that I thought, well, maybe I should paint full-time. And I had a problem, which is that I actually was good at the beginning. My first six months, I would say, painting, I was a much more successful painter than I ever was again.

Debbie Millman:

Why?

Adam Moss:

Because I was looser, because I was naive. I didn’t know better. Really, I can’t believe how thematically consistent this all is. And then as soon as I did know more, as soon as I took more classes and that kind of thing, my work started to just stiffen up and fall off a cliff. So that was deeply, deeply upsetting to me, and though I enjoyed it, it scared me.

Debbie Millman:

Why?

Adam Moss:

Because I really wanted it and I didn’t know how to get there, and I didn’t have any roadmap whatsoever to get there. I mean, I could acquire skills, but I was already, I think, aware that skills training wasn’t the problem. I mean, I did lack skills, but you can always get skills. I really felt that there was a way of thinking as an artist and a degree of courage and risk-taking that I did not have in solo activity. I’d had it in a group because the group is safe, and the group eggs you on and making something together in a group is really still the greatest thing in the world to me. But here I was alone and not making enough progress. So that’s really when I realized that I just wanted to talk to people who were successful at making art, and by art I mean any art, novels and poems and visual art.

And then I was afraid that they wouldn’t be truthful with me, they wouldn’t know how to be truthful with me because so much of the process of making art secretive and people are afraid of jinxing the muse so they develop a set spiel. And that’s how they talk about their art, and it’s about the project and all of that stuff. But that’s not what I wanted to know. I really wanted to know how something is made and what goes through a person’s mind when they’re making it, and what goes through a person’s emotional makeup. What kind of person is successful at this? So that’s when I devised this idea of concentrating on a single work from each of these people and asking them to trace the evolution in as many different layers as they could, both practically what they did, but also very much their emotional journey.

And then also part as a go to help them remember truthfully, and also just because I love this stuff, to accompany it with a gallery of the artifacts of the making of the thing, the notes and the sketches and the doodles that were their tools, making the work. Then I looked at all that, and I had a book, or I had a structure of a book, or I knew what the book was.

Curtis Fox:

Adam Moss’s book is called The Work of Art: How Something Comes From Nothing. David Remnick has been the editor of the New Yorker Magazine since 1998. Debbie spoke with him in March in front of a live audience at the On Air Festival in Brooklyn.

Debbie Millman:

It took three years, but the magazine has actually been profitable since 2001.

David Remnick:

Look, I will say this, our business changed a lot. The old style of all magazines was subscriptions were very cheap so that it would get in a lot of hands, and so advertisers would reach as many people as possible of a certain audience depending on what the magazine was or newspaper or television network or whatever it might be. The nature of advertising has changed and is completely and utterly dominated by Google and Facebook. I don’t know what the real numbers are, but something like 75% of the ad market is to that, and the rest is scraps. And the result has been, in addition to other factors like Craigslist and so on, has been the decimation of mid-level newspapers. I mean, there’s really only a few exceptions to this, and magazines, and it’s tragic. It’s tragic. Not that every publication that’s been lost or diminished is perfect, but the changed landscape is deeply, deeply, deeply worrying for all kinds of reasons that we can talk about.

The only other alternative that I know of at the moment is subscriptions. Same thing that television’s discovered. And luckily enough, fairly early we changed our emphasis and we basically said to you, readers of the New Yorker, without saying it, that I can’t give this away anymore. You have to pay more than a cup of coffee a week to have this extraordinary thing in your hands or on your phone or whoever you choose to read it. And the New Yorker, in fact, gives you a great deal more per day, per week than when Mr. Sean was editing it. But the subscription model, now that we’ve had a lot of success with it for a while, now, the subscription model is facing challenges too, because you’ve all had this discovery. You’ve all woken up and go, wait a minute, I have Netflix, I have Paramount+, I have da-da-da. And then there are even apps now to get rid of or shave down your subscriptions.

Debbie Millman:

Which was the original cable system.

David Remnick:

Exactly. So we’re in a time of real flux, and editors spend a lot more time thinking about business than they probably, if they’re being honest with themselves, would like to. They want to be thinking about writing and graphic design and all kinds of things, but if you don’t have your eye on business, and this goes with public radio or look at what’s happening in the podcast business, we have the New Yorker Radio Hour with my colleague David Krass. Now, we have a terrific time doing this. We’re thinking about how to develop it, make it better all the time, but we also have to pay attention to economics. Otherwise, you wake up and something terrible’s happened.

And I’m determined. We are going to celebrate a 100th anniversary next year at the New Yorker. I don’t want that to be an occasion for us to show off at a museum of ourselves. There’ll be some of that to be sure, but I want people in this room and their children to be reading the New Yorker that is a lot better than the one that we have now in the future. So I think about that kind of thing all the time.

Debbie Millman:

The last thing I want to talk to you about is music. In your latest book, Holding the Note: Profiles in Popular Music, you state that there’s no one who has meant more to you than Bob Dylan. In 2004, you were hoping to get an exclusive excerpt of his recently published memoir in the New Yorker. You almost had it in the bag.

David Remnick:

Yeah, I got screwed with my pants on.

Debbie Millman:

Dylan wanted the cover. Dylan wanted the cover of the New Yorker.

David Remnick:

Let’s just say that Bob Dylan has remained unmoved by and unimpressed by my hero worship. It doesn’t keep him up nights. Apparently, I’m not alone. So what happened was I had heard that he was writing a memoir and that it was good and that it wasn’t like Tarantula, which is a, I don’t know, surrealist experiment. And I was summoned. I said, “Well, send the manuscript to the publisher.” He said, “I can’t send the manuscript. It would be like sending the Dead Sea Scrolls to my apartment.” So I went to the Dylan office, I won’t even tell you where it is, but you have to press a button that says, I don’t know, “AB Cube carpets.” It’s like a CIA thing. And you go up there and it’s just Dylan everything, Dylan tote bags and Dylan albums and Dylan this and Dylan that.

And if I had gone when I was 16, my head would’ve exploded into 1,000 pieces. And they sit me in a little room with a bare table and a manuscript and a glass of water, and I sat there and read the book straight through, Chronicles [inaudible 00:24:51]. And it was terrific. And I said to the publisher and the Dylan Guy, nice people, “I’m in. Don’t call Rolling Stone. That’s not your audience anymore.” I don’t know, whatever bullshit I told them. I was trying to get it for the New Yorker. I’m a competitive person. And we made an agreement and we made a handshake agreement. Okay. And it still pisses me off.

Debbie Millman:

I know.

David Remnick:

It was many years ago. John Kerry was running for president. Half the people here weren’t born yet, and it really pisses me off, this thing. And it got to the summer and they call and they say, “Okay, we’re about to publish it.” And I said, “Great. 7,000 words. The New York bit in the beginning. We’re all set. We’ll try to figure out what to do about fact-checking and copy-editing. Bob doesn’t necessarily have to be completely involved,” and so on and so forth, whatever shit I was slinging. I just thought, everything’s going to be great. And then they said, “Bob wants a cover.” I said, “Bob wants a cover. We have dogs on the cover or a bowl of fruit or a joke, or a Barry Blitt making fun of whatever. We don’t do that. We don’t have photographs on the cover.”

And I thought I’d changed their mind. And there was a pause and they said, “Bob wants a cover.” And it was like talking to your parents at your worst, “Bob wants a cover.” I said, “I can’t do it.” I said, “I’m sure we can find some way to work this out.” “Bob wants a cover.” And that was it. They went to Newsweek, and by that time Bob looked like Vincent Price with the little mustache and the cowboy hat. And I thought, they’re never going to put Bob Dylan on the cover.

Debbie Millman:

It’s an election year.

David Remnick:

It’s the middle of a presidential race. They put on the cover and they ran this excerpt and apparently Bob Dylan survived the experience of not being published in the New Yorker. And then another thing happened, I saw that he had these paintings. He’s a painter. He also makes whiskey and iron gates, a man of parts.

Debbie Millman:

He’s got range.

David Remnick:

He’s got range. And these paintings, some of them are good. And there was one, a painting of Katz’s Delicatessen, the pastrami capital of the world, and it’s pretty good. And it’s a good New Yorker cover. It’s a New York scene. I make an arrangement. We’re all set to go. Two weeks out, I get a phone call. Bob doesn’t want to do it. So I feel our relationship is not on an equal level somehow.

Curtis Fox:

David Remnick. Scott Dadich is a designer, a filmmaker, and a magazine editor. He went from creating the tablet edition of WIRED Magazine to becoming the magazine’s editor-in-chief for several years.

Debbie Millman:

Some of your biggest accomplishments at WIRED were the collaborations you forged with guest editors and your exclusive interviews, and somehow you were able to get an exclusive sit-down interview with Edward Snowden in Moscow, and you wrote this about the experience. “Just a few people on Earth know where I was and why in Moscow to sit down with Edward Snowden. It was a secret that required great efforts to keep. I told co-workers and friends that I was traveling to Paris for some work, but the harder part was covering my digital tracks. Snowden himself had shown how illusory our assumption of privacy really is, a lesson we took to heart, that meant avoiding smartphones, encrypting files, holding secret meetings. Scott, how did you get that interview in the first place?

Scott Dadich:

That was a process that took probably the better part of eight or nine months. My very dear friend, Platon, long-time collaborator dating back to my earliest days at Texas Monthly, and I had talked about this as a get. This is a thing, and we thought in first terms of the visual, and we thought in first terms of the cover, very much in a George Lewis condition, like we need to make an iconic cover, and this is a moment and an individual who would deserve such a treatment. Then came the very real practicalities of what he had or had not done, and the arguments in the newsroom about our obligation to cover his actions, whether we agreed with them or not, whether we could reach him or not. But it was my responsibility as the editor of WIRED to reach out and to find a channel appropriate to find him.

We were looking at news reports and wire clippings and the access that The Guardian was getting and what we’re seeing on channels like social media and Twitter. So we had some indications, but ultimately got a connection that Platon and I had raised to an individual who knew his lawyer. And so we got a communication over to him, and we waited and we checked in and we waited and we checked in. I don’t remember the exact date, but we got a communication back that if I were to be in Moscow on such and such a date at such and such a time at such and such a hotel, maybe conditions would be right for a meeting.

Debbie Millman:

And you and a photographer went, I believe?

Scott Dadich:

Yeah. So Platon, the photographer, we packed up some cases and his assistant and our photo editor we all met in Moscow. And the secrecy and the skullduggery of it seems over the top, or maybe to some seemed over the top at the time, but I did have to communicate to a couple of my colleagues at Conde Nast. And I also sought the advice of several of the other editors-in-chief that I had trusted very deeply and have very strong relationships given my previous work with them. So I just sought some advice and it turns out that a couple of them, and one of them in particular had been over in Russia and had been hacked and had his smartphone compromised, and banking details and all the things that you can imagine would be really terrifying to encounter. So there was a very real cautionary tale about why the secrecy was going to be required. Whether it was from people chasing Snowden or other actors or government officials, we just didn’t know, and there was a lot to be careful about.

Debbie Millman:

Did you know for sure he was going to show up or was it, were you just hoping he’d show up?

Scott Dadich:

We really didn’t, and we were hoping. And I did, we stopped in Paris, and I met Platon at Charle de Gaulle at the gate, and I had sent my iPhone back in a FedEx packet back to Amy in San Francisco. And so I was phoneless until we got to the Moscow airport. Platon and I bought burner phones and no one knew those numbers. No one knew how to reach us. We were there. We did not bring computers. We were not online. We left no digital signatures. We checked into that hotel and we waited. We sat and we waited, and sure enough, the phone rang and it was Ed himself. And this voice on the phone at the pre-appointed time called out and said, “I understand you’re in room so-and-so and I’ll be there in about an hour.” And sure enough, there was a knock at the door about an hour later, the longest hour of my life waiting to see if that was going to happen, and he ended up showing up.

Debbie Millman:

Scott, as an interviewer, I need to ask this question. It might not be as interesting to my listeners as it will be to me, but I can’t resist. How did you prepare for that interview?

Scott Dadich:

Well, obviously, we had just read everything we could get our hands on, stayed as current as we could on news events, on government positions and what the Obama administration was doing. Obviously, we have an incredible amount of opinion and reporting background from our colleagues in the newsroom, so you feel pretty well-prepared. I was there not only to meet with him, oversee the photo shoot, and then facilitate the interview for Jim Bamford, our incredible journalist who’s going to write the profile. Jim was also there and meeting with him the next day. But Platon and I ended up having the very first interaction with him in that hotel room, which lasted about four hours that afternoon.

Curtis Fox:

Scott Dadich. You can hear the full interviews with all four of these editors on designmattersmedia.com or wherever you get your podcasts. Design Matters is produced for the TED Audio Collective by Curtis Fox Productions. The interviews are usually recorded at the Masters in Branding Program at the School of Visual Arts in New York City, the first and longest-running branding program in the world. The Editor-in-Chief of Design Matters Media is Emily Weiland.